A Brief Biography of Jonathan Fisher

Jonathan Fisher, self-portrait (1824).

Jonathan Fisher (1768-1847) was born in New Braintree, Massachusetts. After the death of his father, a Revolutionary War soldier, he was reared in the Holden home of his uncle, a minister. As a young man he considered becoming a blacksmith, cabinet maker or clockmaker, but his intellectual gifts were evident, and his family was able to send him to Harvard in 1788.

In 1796 he became the first settled Congregational minister of the small village of Blue Hill, Maine. Although his primary duties as a country parson engaged much of his time (followed closely by farming), Fisher was also an artist, scientist, mathematician, surveyor, and writer of prose and poetry. He bound his own books, made buttons and hats, designed and built furniture, painted sleighs, was a reporter for the local newspaper, helped found Bangor Theological Seminary, dug wells, built his own home and raised a large family.

A painting by Jonathan Fisher.

Painter & Engraver: The Artistic Endeavors of Jonathan Fisher

Jonathan Fisher claimed that his artistic talent developed because of his passion for mathematics and geometry, and his need to work on such problems by drawing out their solutions. In his autobiographical Sketches he states:

Between the years of 10 and 15 of my age I began to exhibit some traces of a mechanical genius and a turn towards mathematics, spending my leisure time . . . in solving various questions in mathematics, sometimes with a pin on a smooth board and sometimes on a slate, which led the way afterwards to a small measure of proficiency in sketching and painting.

Fisher illustrated many of his college notebooks with vivid watercolors. The parson later collected these pages and bound them into volumes, many of which remain in the possession of the Jonathan Fisher House. Fisher also painted views of Harvard College—which he sold to augment his humble income as a student—as well as numerous illustrations of animals, plants, and other scenes of natural history.

Fisher learned to paint with oil on canvas. He produced landscapes, portraits, and images of nature, and he painted several still lifes at a time when few Americans practiced that art.

The parson also made numerous engravings and built his own press on which he could strike prints. Fisher, as often was the case, turned his talent to commercial use and sold several of his woodcuts to local newspapers. His masterpiece in the medium was a natural history book written for children, Scripture Animals, which depicted every creature named in the Bible.

Bitterns, (from Scripture Animals, 1834).

Engravings

Jonathan Fisher began making woodcuts in the summer of 1793 while home on vacation from his studies at Harvard. His journal entries from the time record the following:

Dedham July 22-27, 1793. Worked on the farm; engraved on boxwood, began a small printing press.

July 29-Aug. 3. Worked on printing press and haying.

Aug. 5-10, 1793. Worked some on the farm. Finished my printing press; engraved a little and struck off a number of prints from boxwood cuts.

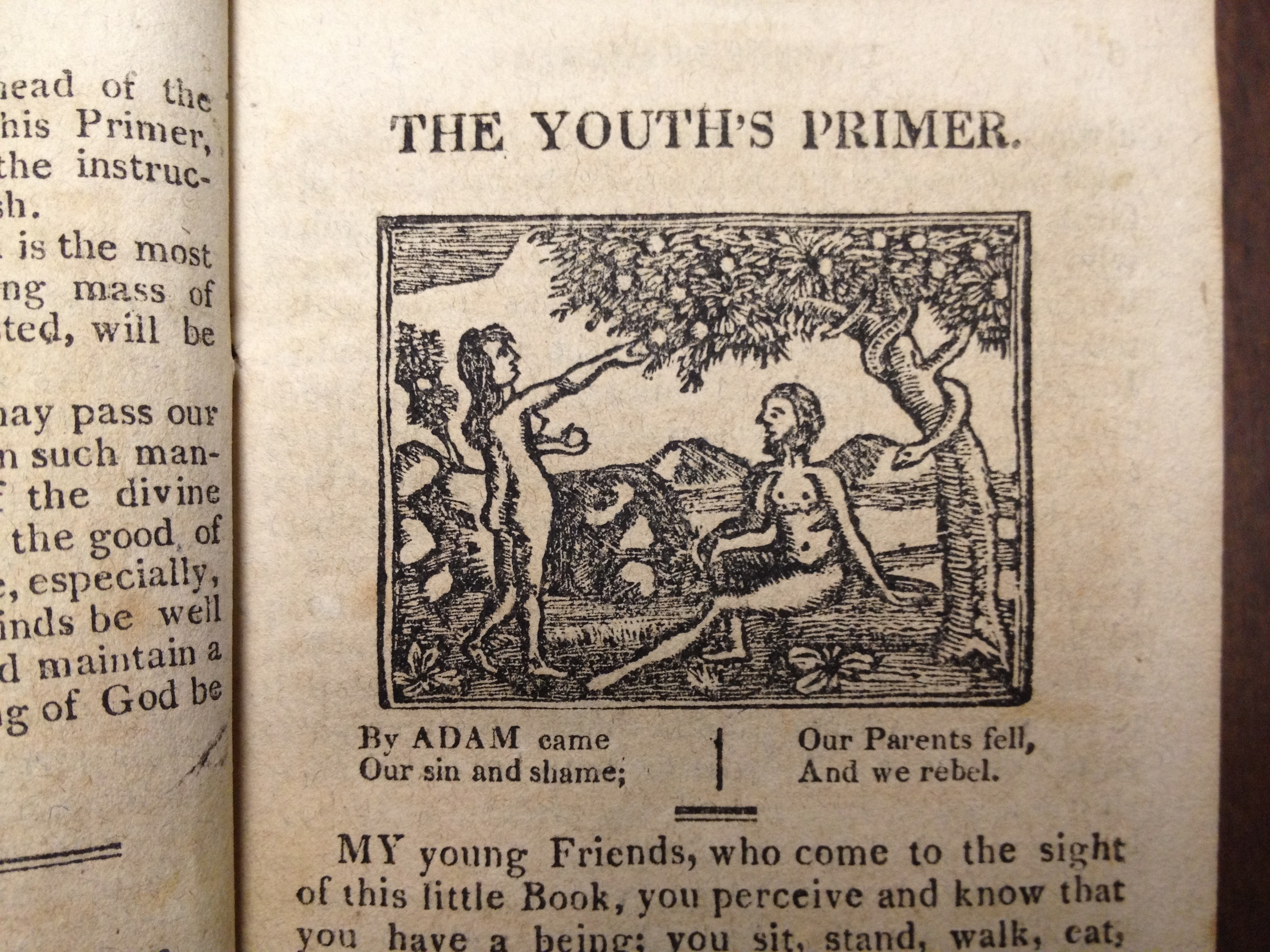

The Youth's Primer, published in 1817.

Fisher illustrated two of his books with his own engravings. The Youth’s Primer, published in 1817 with 28 engravings, was patterned after the New England Primer. Scripture Animals, published in 1834, took 15 years to compile and was filled with 140 woodcuts depicting each of the creatures mentioned in the bible. Fisher’s preface to the volume states:

As respects the cuts, a few of them are from nature, but most of them are copied, and generally reduced a little, to bring them conveniently within the compass of the page I have chosen for the work. Of the execution, I may remark, that not being able to hire them engraved, I have engraved them myself, and having had no instruction in the art, and but little practice, I can lay claim to no elegance in their appearance. I have endeavored to give a true outline; the filling up must speak for itself.

Fisher also engraved a bookplate for the Blue Hill Library—still used to this day—as well as stamps for the Blue Hill Academy and the Congregational Church Library.

Karl Kups, curator of prints at the New York Public Library, characterized Fisher’s engravings in these terms: "Fisher’s style of engraving, in the manner of the typical primitive, shows the lack of training, of “how-to.” But it is made up by a most fervent desire to please, and by an almost childlike persistence to get that animal upon the wood block, come what may. His modeling is poor . . . but in the handling of the tool . . . Fisher shows real craftsmanship in the execution of his engravings. He knows no fear in flicking out small bits to get the texture of either fur or feathers. He engraves the most enchanting landscapes around and behind his animals . . ."

Early (c. 1790) Fisher watercolor of Harvard College.

Watercolors

Jonathan Fisher set down specific directions in his early notebooks regarding painting in watercolors, which he was already attempting soon after his arrival at Harvard:

Painting in water colors. The materials necessary for this art are gum, colors, hair pencil, fitches, a pallet, and pen knife. The colors in general are white, black, brown, red, yellow, blue, and green.

Directions for using the colors. Your pencils must be fast in their quill, and sharp-pointed after you have drawn them thro' your mouth. Before you begin, have all your colors ready before you, and a pallet for the conveniency of mixing them; a paper to lay under your hand, and to keep your work clean, as well as to try your colors upon; also a large brush, called a fitch, to wipe off the dust, when your colors are dry. Lay your colors on but thinly at first, deepening and mellowing them by degrees as you see occasion. The quicker you lay them on, the evener and cleaner your drawing will appear. Take care to preserve all your colors from dust; and before you use them, wipe you shells and pallet every time with a fitch. When you have done your work, and would lay it aside, be careful to wash out your pencils in warm water.

The parson also gave detailed instructions on how to paint human faces and landscapes. Some at least of his advice was copied directly from The Art of Painting in Water-Colours, originally published in London in 1786.

Today the largest preserved bodies of Fisher’s artistic works are owned by The Fisher Memorial and by the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, Maine.